"The free market failed."

"Greedy businessmen have ruined us all."

"The age of capitalism is over."

Such are the explanations that surround the collapse of the financial and real estate markets from 2007 to 2008, shortly followed by a nationwide recession. Big banks and speculators had made too many risky investments, we are told, and lost their fortunes, putting at risk the entire economy. At the surface this is indeed what took place to set up the crisis. The whole truth, however, requires far more than a surface-level understanding of the boom and bust of the 2000's. To gain an understanding of what happened during the economic bust, one must first understand what took place beforehand--the economic boom

This is the first of a three-part series detailing the complete failure of government intervention and the innocence of the free market in the buildup to the current economic crisis.

Boom and Bust

Normally, there are two parties principally involved in the process of purchasing a house: the buyer and a lending institution of some sort. The buyer, unless he is filthy rich, needs to get a loan with which to buy the house, and the lending institution is more than willing to provide him with that loan, with interest. The buyer takes the loan, buys a house, and spends several years slowly paying the mortgage.

The times from 1998 to 2006, however, were not "normal." Housing prices increased dramatically. Houses became the "best investment," because "they never lose value." Speculators and house-flippers bought low and sold high, riding the waves of the economy. Precious few suspected the boom was merely a bubble, prone to popping at one point or another. Yet, despite the doubts of the vast majority, the minority was proven correct. In 2006, home prices and stocks began to decline, then freefall. By 2009, multiple bailouts of failing industries, "stimulus packages" for the groaning economy, and increased regulation of the financial industry were deemed necessary to "save capitalism."

Fannie and Freddie

Most everyone assumed that the collapse was due to the wild swings of a normal, free-market economy. Yet, as I stated before, nothing was normal in the usual sense of the word during the housing bubble. Government intervention ran rampant during this time period, and two key pieces to the government puzzle are the corporations known as Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. These corporations, known as "government sponsored enterprises", were technically private but were given governmental powers over the housing market.

Their primary function was to purchase mortgages from lending institutions. Lending institutions would then receive a large sum of money up front, while Fannie and Freddie would receive the steady income from the debtor and hold responsibility for that loan and the possibility of default. Once Fannie and Freddie had accumulated a large number of loans, they would repackage them as "mortgage-backed securities." These were essentially several loans bundled together and sold on the market to investors. Critical to these securities was the diversity of the loans packaged inside them; there had to be a wide variety of loans, some safe, others much riskier.

Absolute Power

Despite the fact that the risky loans were packaged together with the good loans, the security as a whole was considered to be safe, or "AAA", by investors and advisers. Why? Political pressure from various government branches pushed independent rating agencies to certify those risky investments in order to stimulate more homebuying; the more mortgage-backed securities sold on the market, the more money banks got from Fannie and Freddie, the more loans those banks could make to potential homeowners.

As will be detailed in Parts II-III of this series, this pressure placed on private rating agencies is just the beginning; political power in its various forms, from Fannie and Freddie to regulation to monetary policy, formed the bedrock of the boom and subsequent bust, and will likely shape the global economy for decades to come.

Wednesday, December 23, 2009

Saturday, December 5, 2009

Spending and Slavery

Starting in December 2007, the United States entered a recession that soon affected the entire industrialized world. Fierce debate has surrounded the Federal Government's response to this downturn. In addition to adjusting financial regulations and monetary policy, the Bush Administration proposed a bill called the Emergency Economic Stabilization Act allowing for $700 billion of assets to be bought from failing banks; the legislation easily passed through Congress. Later, the Obama administration passed the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act through Congress, a $787 billion "stimulus" package, in addition to extending credit to failing automakers even to the point of nationalizing General Motors.

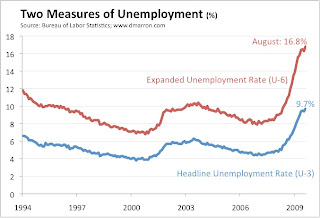

While the Obama administration predicted that the unemployment rate from the recession would never get higher than 8.1% thanks to his and his predecessor's spending(1), the official unemployment rate had leaped up to 9.7% by August 2009, and unofficial studies said the rate was actually 16.8%, over twice as high as the original estimates(2). What happened? Why did the government spending fail to improve economic conditions?

First, proponents of Keynesian spending (such as Bush's and Obama's) fail to realize that government spending to "create or save" jobs only creates temporary employment. Unemployed people who are put to work thanks to government projects such as highways and other infrastructure will work for a few months, then suddenly be back out of a job again after the spending on that project stops. As a result, jobs created thanks to the government are never permanent unless the spending is also permanent.

Second, any government's spending is vulnerable to corruption and abuse. In November 2009, a massive scandal erupted regarding the locations where the Federal government had put the stimulus money from the ARRA. At the White House's own website, recovery.gov, reports could be found of stimulus money going to congressional districts that didn't even exist. Billions went to places such as the "0th District of New Hampshire" and the "15th District of Arizona", which are completely nonexistent(3). This is to be expected when a group of individuals with special interests, such as politicans, are given the authority to deal with large amounts of money.

Lastly, Keynesianism ignores the fact that private investment is much more effective than government investment. Because the government is rarely subjected to a price mechanism as often as the private sector and does not necessarily need to balance its budget, the government can spend and spend and spend without having the slightest impact on the economy. Private individuals, who have a bottom line to meet and a budget to follow, are more likely to target the places they spend and invest in with care, doing business with ventures that provide superior products and services or are most likely to succeed and therefore deserve investment most, while leaving badly-run businesses to fail.

In light of this last observation on private investment, tax cuts provide an excellent mechanism for the private sector to invest more money during an economic downturn. Tax cuts also provide benefits aside from leading to more efficient investments. First, tax cuts provide a 100% assurance that people will be able to spend on things that they want. If the ultimate purpose of growing an economy is to improve the quality of life of a large portion of the populace, tax cuts are the most definite way of doing so.

Finally, tax cuts give back to the people what is already theirs. Stealing is considered morally reprehensible in nearly every culture, yet it is somehow excused when it is done by government and approved by at least 51% of the people. Yet the presence of a government changes nothing; taking someone's hard-earned private property is stealing regardless of whether the thief wears a mask and lives on the streets or wears a suit and works for the IRS. There are indeed benefits to government such as public services and the defense of justice that can only take place with taxation, but they are still funded by wholesale robbery that should be kept to a minimum. The morality and economic practicality of tax cuts simply go to show, once again, that a hands-off approach to the economy and indeed to society as a whole is both the most practical in terms of improving quality of life and the most moral in that it recognizes private property. Liberty is, and always will be, the best policy for a government to follow.

1. http://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/assets/fy2010_new_era/Summary_Tables2.pdf

2. http://voices.washingtonpost.com/economy-watch/2009/09/actual_unemployment_rate_hits.html

3. http://abcnews.go.com/Politics/jobs-saved-created-congressional-districts-exist/story?id=9097853

Friday, December 4, 2009

Guns and Butter, Round Two

In the tumultuous presidency of Lyndon Baines Johnson, politicos typically referred to Johnson's twin policies of increased intervention in Vietnam and expanded social programs as "guns and butter." While the financial toll of these two fronts separately may have been steep, but bearable, both of them put together brought the American economy to its knees, putting the entire country through a steep slump.

A mere 10 months into his administration, President Barack Obama faces a similar decision: he fights a war allegedly critical to national security in the wilderness of Afghanistan while pushing for health care reform in the even wilder Washington, D.C.. Obama recently called for 30,000 additional troops to be sent into Afghanistan, bringing the total troop level in that country to approximately 98,000, while the level of private contractors is roughly 104,000. On top of it all, official estimates of the $30 billion cost of the buildup is cause for major concern.

Lost in all these big numbers is the little fact that there may very well be fewer than 100 members of Al Qaeda in all of Afghanistan. Add the $30 billion for the troop surge plus the $65 billion already being spent annually on the war in Afghanistan, and do the math: the United States is spending--wait for it-- $950 million per Al Qaeda operative in Afghanistan, per year.

On the home front, the Congressional Budget Office has warned Senate and House Democrats that their proposed health care overhaul will raise costs, not reduce them, and add to the already heavy financial burden. The estimated cost of $1.5 trillion over a decade can only be paid for by raising taxes, borrowing money, or inflating the currency, all three of which are bad options for a president overseeing an economy badly in need of a boost.

All these costs will add to the record $1.8 trillion deficit forecast for the year 2010. Add on to all this gloom and doom the $12 trillion-and-counting national debt and our untold trillions in unfunded liabilities from programs like Medicare and Social Security, and suddenly Obama's war in Afghanistan and health care proposal don't seem like such good ideas even separately, much less combined.

Johnson tried too hard to force his statist agenda on America, and it very nearly broke the country's back. Obama must escape his fantasyland which history can be ignored, and stop to consider the consequences of enacting not one, but two massively expensive programs which, depending on who you ask, are probably not worth the cost even if enacted in better circumstances.

Friday, November 27, 2009

Why Your Packages May Soon Cost Twice As Much

For the past several months, FedEx and United Parcel Service (UPS) have been in an intense legal battle that could shake the entire shipping industry. FedEx, because it ships the majority of its packages via air, is governed under different unionization rules than UPS, which ships the majority of its packages via trucking. As a result, FedEx's labor must have a majority of all its employees voting in favor of organizing in order to unionize, while UPS' labor need only get a majority of the employees who actually vote.

UPS' costs in worker compensation are now over twice those of FedEx.

UPS and the Teamsters are now lobbying Congress to reorganize federal labor laws in a way that will bring more of FedEx's workers into the same designation as UPS' workers and therefore, bring all of FedEx under new labor regulations.

The exorbitant costs that the unionization in UPS has brought are no surprise; for decades unions have exerted enormous power over business and government, lobbying for power, more power. Yet some misunderstand the unions' problems as problems of existence. "If we could just get rid of the unions," they reason, "we could get back down to business again." This, however, ignores the basic reason of why the unions have gained so much power in recent years. In the Industrial Revolution, when unions were just starting to pick up steam, businesses used their political clout to gain benefits from the Federal Government in the area of labor management (case in point: when President Hayes sent federal troops in to put the kibosh on the workers participating in the Great Railroad Strike of 1877). The situation between labor, government, and business was like this:

LABOR --- GOVERNMENT == BUSINESS

In response to the overwhelming power of the alliance between business and government, labor unions began to realize the power of lobbying for themselves and soon, various groups of both labor and big business were vying for government handouts and favorable regulations.

LABOR == GOVERNMENT == BUSINESS

In time, particularly as the Progressive Era of Teddy Roosevelt, Woodrow Wilson, and later FDR gained power, business still received favorable government action such as subsidies and competition-squashing regulations, but lost much of its power in the area of organized labor. Meanwhile, unions gained more and more political power as the Great Depression provided a pretext for the increasing of labor power. This situation has continued to the present day, with this relationship between labor, government, and business:

LABOR == GOVERNMENT --- BUSINESS

Unions can now use the coercive authority of government to force employers into deals that hurt business, consumers, and indeed, non-union workers. As a result, products and services cost far more than they should and these costs are either passed on to consumers or kept within the company until the company fails. Now the economy is in no better a situation than it was when employers held the power to take away workers' rights by using the government as a weapon.

The appropriate solution is one in which government stays out of the dealings between businesses and their workers. Freedom of association is the ideal situation, in which workers can stay in their job if they wish, but also have the liberty to leave if their employer is giving them unfavorable conditions.

The appropriate solution is one in which government stays out of the dealings between businesses and their workers. Freedom of association is the ideal situation, in which workers can stay in their job if they wish, but also have the liberty to leave if their employer is giving them unfavorable conditions.

LABOR == BUSINESS

Simply abolishing unions and other forms of organized labor will not solve the problems currently faced by employees and their workers. Doing so would simply be a return to the old days in which businesses held complete control over their employees and the working class suffered. Instead, one should look to the root of the problems in modern industry, which is an overbearing, intervening government that has given itself the role of mediator between business and workers, a mediator that nobody wants.

Thursday, November 26, 2009

Things to be thankful for...

It's all too easy to be caught up in the gloom and doom of the state of American politics--and indeed world politics--these days. Stories of wars, corruption, economic turmoil, and party divisions dominate the news media today, but often we ignore the bright spots that appear in the cloudy sky. Here are just a few thanks-worthy bits of recent (and not-so-recent) news, info, and thoughts:

- 222 years, 70 days ago, the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia ratified the Constitution.

- On January 23, 2009, President Barack Obama signed an executive order for the closing of Guantanamo Bay Detention Camp.

- In 1841, thanks largely to the efforts of President Andrew Jackson, the Second Bank of the United States went bankrupt.

- On November 19, 2009, Congressmen Ron Paul (R-TX) and Alan Grayson (D-FL) successfully added amendments to House Resolution 3996 to allow for increased audit authority over the Federal Reserve.

- On December 2, 1823, the United States adopted the Monroe Doctrine

- In New York's special election for the 23rd congressional district, third-party candidate Doug Hoffman gained 45% of the vote, losing but gaining significant support.

Wednesday, November 25, 2009

Civilization and its Governments

Philosophers generally hold two clashing views of humanity: one optimistic, the other pessimistic. Each of these viewpoints is often held as an argument to increase the authority of government, whether in economic policies, personal lives, or civil liberties.

The optimistic view of humanity holds that people are inherently good, and indeed are perfectible creatures. All that is needed for a utopian existence is more time for mankind to iron out its faults and get its act together. This view is commonly held by modern liberals, who see government as the ideal "ironing board" to stretch people over and get rid of their problems. The only problem with this is that if people are inherently good, why do they need government to solve all of their problems? People could live in peace with each other without state regulations and taxes and other government functions; they wouldn't need any motivation to help out their fellow man on the street and they would most certainly not attack each other, either personally or militarily.

Clearly, however, this has not happened. Poverty still strikes many. Militaries and insurgents still clash. World peace has not been achieved, world hunger has not been solved. So this philosophy of humanity strikes out. This leaves the pessimistic view of humanity, which states that people are fallen, corrupt creatures with a near-infinite capacity for wrongdoing. This, of course, may be true, as it is the only logical conclusion remaining after the discarding of the optimistic view of humanity; however, this truth is often twisted to provide a false and fallacious view of government's role in society. If humanity is corrupted, one may reason, then it needs a master to keep it in line, right? This view is commonly held by conservatives, who say that mankind's original sin means that government needs to step in and make people do the right things, whatever "right" may be.

However, this view fails to realize that there is no distinction between the corrupt humans of the citizenry and the corrupt humans of the government. If humans are inherently wicked, and governments are comprised of humans, then governments also are wicked. It does not matter whether or not those at the head of the government were democratically elected or seized power in a violent coup; they are just as fallible and prone to mistakes as those they rule.

Both the views lead to an incorrect view of the people; they view people as clay to be molded by a government that is always correct and never falters in its careful control over the citizenry. They both ignore the fact that humans, regardless of election, birth, or status, are all equally prone to evil. The solution to this is to have each man in control of as little of another man's rights and property as possible. Private property must be protected, as must rights and civil liberties, for if any of these things becomes subject to the rule of a privileged few, the only thing that can result is tyranny, oppression, and civilization-wide collapse.

Saturday, November 14, 2009

Physics and the Fry Guy

My house, though upwards of forty years old, is a sturdy old place. I could walk out back, do some stretching, maybe a quick warmup, then push with all my might against its walls, but it wouldn't do a thing, no matter how hard or how long I pushed. I could come back inside at the end of the day having pressed against the house's walls from sunup to sundown, but have nothing to show for it except blistered hands and a sore back.

But I don't do this pointless exercise. Why? Well, aside from the fact that I have no interest in demolishing my childhood home, I also happen to know a bit of elementary physics.

The equation Work = Force x Distance explains why all my blood, sweat, and tears won't budge make the slightest difference in my house's end position. Force can be broken down into two separate components, mass and acceleration. Therefore, force represents the mass of the object I am trying to move (my house--several thousand kilograms) multiplied by the amount I want the object to accelerate. Now, I can put as many Newtons (units of force) into the wall as I want, but if the distance doesn't change, no work has been done and the walls of my house thankfully stay put.

Now, let's apply this principle to labor and income.

"Why does my manager get paid so much more than I do? I work just as hard as he does but he gets paid ten times more than I do! And he just sits in an office all day!"

The entry-level employee may put just as much, or even more, work into his job every day, but what is the difference between the results he gets and the results his manager gets? Take a fast-food restaurant as an example. The fry guy probably works as hard or harder than the manager. He stands in a hot kitchen for several hours a day. He deals with irritable fellow employees and downright stupid customers. He probably has a few burns on his hands from handling grease. The manager, on the other hand, deals with paperwork, gets to talk with people who are actually polite, and rarely suffers anything more than a papercut. So the fry guy should get a higher salary, right?

Wrong.

If the fresh-out-of-high-school fry guy is removed from the scene, the restaurant can still function, and will only suffer a slight loss in performance. Training a new employee of his skill level will only take a short amount of time and a small amount of money. If the manager, however, with years of experience and expertise, is taken out of the picture, the restaurant will not be able to function coherently. In all likelihood, the place will not be able to compete with the opposition anymore and will therefore fold like a house of cards.

So who, in the end, achieved more work? The fry guy puts a lot of force into his job, but will likely never create greater profits for the company than the manager does. The manager has earned his position from having patiently gone through many of the same trials of the kitchen when he was just starting out on his new job. While increased effort will likely increase one's salary, results are what employees are paid for in the end.

But I don't do this pointless exercise. Why? Well, aside from the fact that I have no interest in demolishing my childhood home, I also happen to know a bit of elementary physics.

The equation Work = Force x Distance explains why all my blood, sweat, and tears won't budge make the slightest difference in my house's end position. Force can be broken down into two separate components, mass and acceleration. Therefore, force represents the mass of the object I am trying to move (my house--several thousand kilograms) multiplied by the amount I want the object to accelerate. Now, I can put as many Newtons (units of force) into the wall as I want, but if the distance doesn't change, no work has been done and the walls of my house thankfully stay put.

Now, let's apply this principle to labor and income.

"Why does my manager get paid so much more than I do? I work just as hard as he does but he gets paid ten times more than I do! And he just sits in an office all day!"

The entry-level employee may put just as much, or even more, work into his job every day, but what is the difference between the results he gets and the results his manager gets? Take a fast-food restaurant as an example. The fry guy probably works as hard or harder than the manager. He stands in a hot kitchen for several hours a day. He deals with irritable fellow employees and downright stupid customers. He probably has a few burns on his hands from handling grease. The manager, on the other hand, deals with paperwork, gets to talk with people who are actually polite, and rarely suffers anything more than a papercut. So the fry guy should get a higher salary, right?

Wrong.

If the fresh-out-of-high-school fry guy is removed from the scene, the restaurant can still function, and will only suffer a slight loss in performance. Training a new employee of his skill level will only take a short amount of time and a small amount of money. If the manager, however, with years of experience and expertise, is taken out of the picture, the restaurant will not be able to function coherently. In all likelihood, the place will not be able to compete with the opposition anymore and will therefore fold like a house of cards.

So who, in the end, achieved more work? The fry guy puts a lot of force into his job, but will likely never create greater profits for the company than the manager does. The manager has earned his position from having patiently gone through many of the same trials of the kitchen when he was just starting out on his new job. While increased effort will likely increase one's salary, results are what employees are paid for in the end.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)